|

|

|

TREKCORE >

VOY >

EPISODES >

SCORPION

PART I &

II >

BEHIND THE SCENES >

Designing Species 8472 Part 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parts 2 and 3

of "Designing Species 8472" describe an interview Foundation

Imaging's John Teska gave to Star Trek Monthly about Species

8472. All quotes are from John Teska

unless otherwise indicated. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The task of

constructing the CGI Species 8472 creature was given to John

Teska at Foundation Imaging. He was ideally suited to the job

because, as well as being a skilled computer modeller, he has a

background in traditional creature effects such as traditional

puppets.

By the time John Teska became involved, concept artist Steve Burg

had already produced a set of drawings that showed what the creature

should look like but a lot of creative work still had to be done. In

fact, the producers handed him several drawings with instructions to

use different elements from each one.

Teska

recalls, "It was something of a Frankenstein's

monster. The key features the things that distinguished the creature

were the three legs, the tendons in the neck, and the basic head

shape, all of which had been laid out in Steve's artwork. I followed

that fairly closely. But, in addition to pulling these designs

together, I had to go in and do deeper detail like sorting out the

colors and working out literally what the flesh would look like -

the wrinkles and things like that. Certainly, there was plenty of

room to put my own ideas in and breathe life into it." Teska

recalls, "It was something of a Frankenstein's

monster. The key features the things that distinguished the creature

were the three legs, the tendons in the neck, and the basic head

shape, all of which had been laid out in Steve's artwork. I followed

that fairly closely. But, in addition to pulling these designs

together, I had to go in and do deeper detail like sorting out the

colors and working out literally what the flesh would look like -

the wrinkles and things like that. Certainly, there was plenty of

room to put my own ideas in and breathe life into it." |

|

|

|

|

John Teska

began work by setting up a very crude version of the creature in the

3D software package, Lightwave.

"As

there were script discussions at Paramount we started to get the

word that there would be a new nemesis that would make even the Borg

afraid. It was exciting that it would be a CG character and that it

would be a major player. When I started to get into the process I

saw some of the sketches being done by Steve Burg. I was excited

because it was non-humanoid. It didn't look like the usual guys with

facial changes. This one had this very strange neck and strange body

structure with three legs. As an animator, a designer or creature

person, I was jazzed about bringing this guy to life. In this case,

Steve Burg had several meetings with Paramount. They had different

designs of things like the arm structure. [...] There were many

drawings. They liked features on each. Paramount and Dan Curry

talked to me about the designs. They said: "Could you put them

together and make a creature?" I didn't have a singular drawing of

the final creature. There was still some evolution as he was being

sculpted in 3D. Once I had the drawings I just did a simple block

shape to figure out the proportions and the size of the head and

body, and I gave it to Paramount, so it was a back and forth thing.

It went from blocky and crude and worked up to the finer points. The

paint mattes and textures were done several weeks later. "As

there were script discussions at Paramount we started to get the

word that there would be a new nemesis that would make even the Borg

afraid. It was exciting that it would be a CG character and that it

would be a major player. When I started to get into the process I

saw some of the sketches being done by Steve Burg. I was excited

because it was non-humanoid. It didn't look like the usual guys with

facial changes. This one had this very strange neck and strange body

structure with three legs. As an animator, a designer or creature

person, I was jazzed about bringing this guy to life. In this case,

Steve Burg had several meetings with Paramount. They had different

designs of things like the arm structure. [...] There were many

drawings. They liked features on each. Paramount and Dan Curry

talked to me about the designs. They said: "Could you put them

together and make a creature?" I didn't have a singular drawing of

the final creature. There was still some evolution as he was being

sculpted in 3D. Once I had the drawings I just did a simple block

shape to figure out the proportions and the size of the head and

body, and I gave it to Paramount, so it was a back and forth thing.

It went from blocky and crude and worked up to the finer points. The

paint mattes and textures were done several weeks later.

I

just started with a bunch of simple boxes and balls and laid out the

basic shape so that I could rotate it, and get a sense of whether it

had the right proportions, before I invested the time to do the

really deep modeling. It's the equivalent of a digital pipecleaner

model. You make it just to see if the creature looks right standing

next to a person - does it have the right thickness in the body, and

so on." I

just started with a bunch of simple boxes and balls and laid out the

basic shape so that I could rotate it, and get a sense of whether it

had the right proportions, before I invested the time to do the

really deep modeling. It's the equivalent of a digital pipecleaner

model. You make it just to see if the creature looks right standing

next to a person - does it have the right thickness in the body, and

so on." |

|

|

|

|

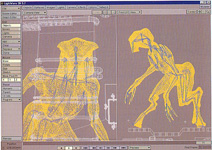

Once he was satisfied with the basic shape, he

constructed a more sophisticated version of his model, shaping the

simple boxes and balls into limbs and muscles. The way Lightwave

works he actually gave the creature a skeleton of 'bones' that were

embedded into the virtual limbs. They were even connected to one

another by joints, which controlled the way they could move. This

skeletal system is very important to the animation process. Because

the bones are connected to one another, the animator only has to

move one of them and Lightwave calculates how the rest of the

skeleton will respond.

"We

animate a lot of the time with what's called inverse kinematics.

That means I'm not concerned with every single bone going down the

leg or the arm; instead I'm dealing with what are essentially

handles - little control points at the end of each arm and each leg.

Kind of like the strings you'd have on a traditional puppet. So he

evolved over the course of his creation. The software we use is

Lightwave 3D. Everything inside of it is treated like real models,

cameras and lights. Building a character like 8472, starting with

the face, I can say "I have a flat shape for the cheek", and create

polygons from the cheek, down the neck and into the body. Everything

in the mind of the computer is a shape, so it's not like I'm

drawing, like in traditional animation. In this case, I'm creating a

model, and even though it's virtual the computer looks at it like

it's a 3D object. "We

animate a lot of the time with what's called inverse kinematics.

That means I'm not concerned with every single bone going down the

leg or the arm; instead I'm dealing with what are essentially

handles - little control points at the end of each arm and each leg.

Kind of like the strings you'd have on a traditional puppet. So he

evolved over the course of his creation. The software we use is

Lightwave 3D. Everything inside of it is treated like real models,

cameras and lights. Building a character like 8472, starting with

the face, I can say "I have a flat shape for the cheek", and create

polygons from the cheek, down the neck and into the body. Everything

in the mind of the computer is a shape, so it's not like I'm

drawing, like in traditional animation. In this case, I'm creating a

model, and even though it's virtual the computer looks at it like

it's a 3D object.

There wasn't a lot of backstory, so I didn't know much about them,

but we knew that they communicated psychically, so I knew there

wasn't going to be a lot of talking. So a key thing was getting an

expressive weird forehead, and a feeling that they were different.

Knowing how they attacked - they're described as really vicious and

able to cause infection just by tearing at you - that is what drove

the animation, trying to make them feel fast and menacing. Whereas

the Borg always had numbers on their side, and had that zombie

"we're going to get you". Species 8472 is more about the surprise

that they'll burst in and start slashing. This character had a kind

of open neck structure with tendons that attach, so it became a

question of how to rig that. The same with the legs. It had three

legs, a kind of tripod structure. I thought about how this guy

walked, but we never actually saw him walk more than two steps. He's

always leaping into rooms and tearing people apart but he never just

walks down a hallway." |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Once the skeletal system had been set up and he had

shaped the musculature, he had a simplistic, and very

smooth-looking, version of the creature. The next thing he had to do

was cover it in a layer of skin; this process is referred to as

'texture mapping'. Effectively, what he had to do was make a

computer-generated jumpsuit and mask for his model. When he wrapped

it around the model, Lightwave gave it textures and contours just

like real flesh. However, as he recalls, for Species 8472 this was

not a simple process.

"The texturing was

technically the most difficult part of it because there are no clear

divisions on the body. Normally, you have clothes or some other

thing to cover up the joins in the maps."

In other words, he had to create the CG skin

in different sections, just as a tailor will make a sleeve and then

connect it to the back and the front of a jacket. However, when you

make a suit no one complains that you can see the seams. Species

8472 was to be naked and thus there could be no explanation for any

obvious joins. The creature was designed several years ago, when CGI

(computer-generated image) technology was much more primitive than

today.

"This

was early on in the evolution of Lightwave, so the choices we had

for texture mapping were somewhat limited. At the time there was

really only one good 3D paint program on the market. That really

saved my butt. It was just a matter of dividing the maps into all

these different pieces, so the arms are painted more or less from

the side, the head is more or less painted like a ball, the body is

treated like a cylinder. Then I had to come back in with additional

paint maps and do a lot of blending between all these different

zones. That was definitely the biggest challenge. What I wouldn't

have given for this guy to wear a T-shirt!" "This

was early on in the evolution of Lightwave, so the choices we had

for texture mapping were somewhat limited. At the time there was

really only one good 3D paint program on the market. That really

saved my butt. It was just a matter of dividing the maps into all

these different pieces, so the arms are painted more or less from

the side, the head is more or less painted like a ball, the body is

treated like a cylinder. Then I had to come back in with additional

paint maps and do a lot of blending between all these different

zones. That was definitely the biggest challenge. What I wouldn't

have given for this guy to wear a T-shirt!"

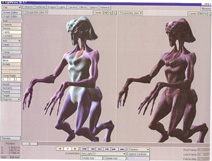

The image above shows what the creature looks like with and without

its texture maps. The model itself is relatively smooth, though many

of the larger shapes, such as the bumps on the head, are built in.

Most of the details, such as the wrinkles in the flesh, are actually

in the texture maps that are used for the skin and are wrapped

around the model as if they were clothes. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<

Part 1 |

Index |

Part 3 > |

|

|

|

|